Blister Beetles

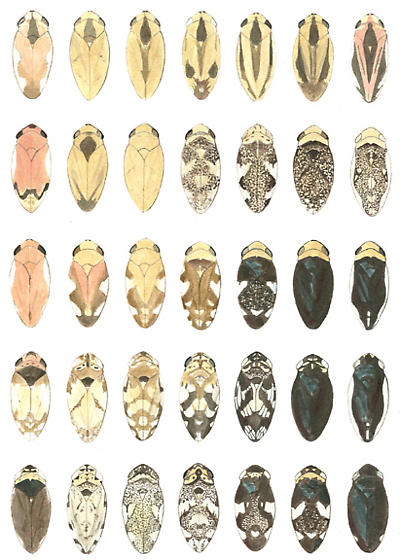

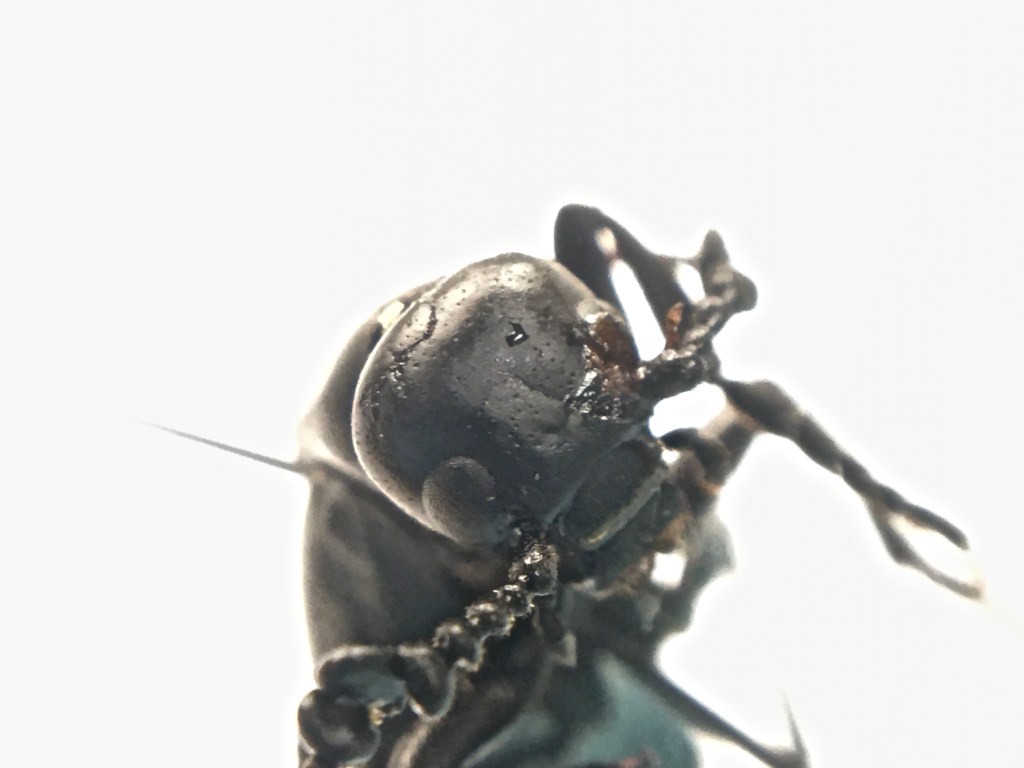

Ventral view

San Juan Island, WA 11/2/2019

I posted back in April about an encounter with Blister Beetles not far from my house. You can read about that here ~ (https://cynthiabrast.wordpress.com/2019/04/16/a-blistery-spring-day/ ). Over the weekend of November 2-3, I came across quite a few more of these in the exact same spot as in April. This time I didn’t see any live beetles, but there were at least 25-30 dead in the road.

San Juan Island, WA

11/2/2019

Ever the opportunist, I scraped up as many that weren’t quite so smushed into a container and brought them home. Out of the 5 I collected, 2 were male, 2 were female, and one missed antennae altogether. Given the number of beetles in the road in this one spot, I believe this was a mating aggregation.

San Juan Island, WA

11/2/2019

So, I’ve been reading about them and communicating with a two experts on blister beetles. If you don’t know what these are, they are significant because of a defensive chemical in them called Cantharidin. Cantharidin is quite toxic and it’s a blistering agent. This is where they got the name Blister Beetles in the first place.

San Juan Island, WA

11/2/2019

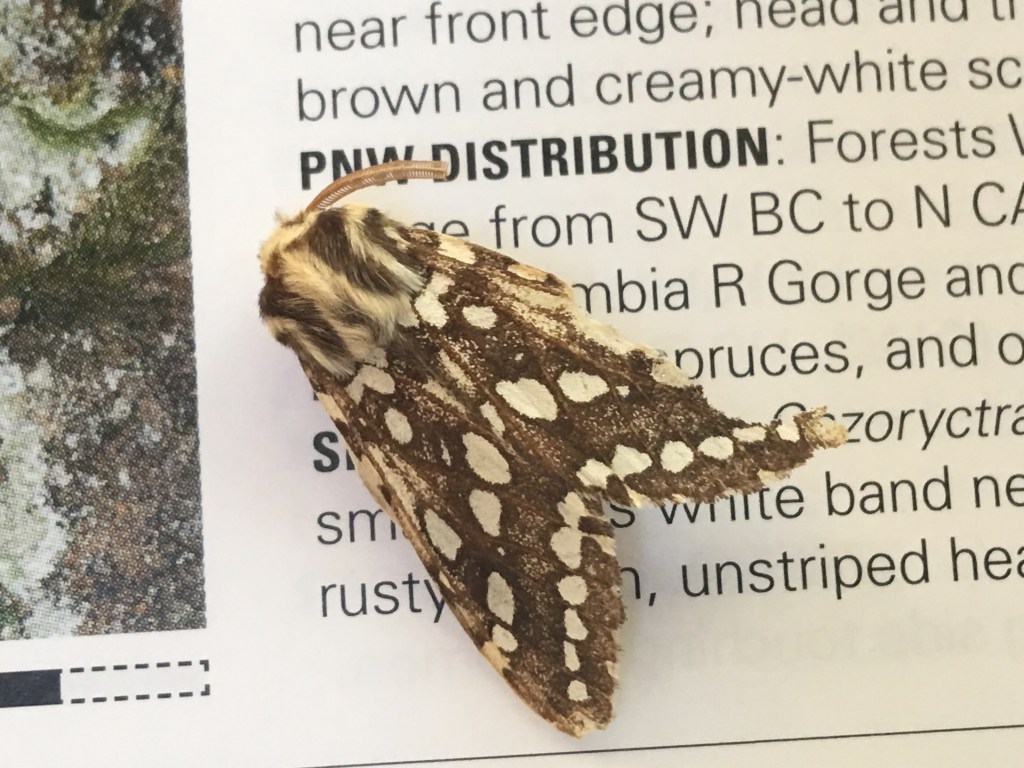

Since my first sighting of these beetles back in April, I’ve learned quite a bit about them. The ones here (Meloe strigulosus) are black, flightless, tanker-like beetles, carrying around a cargo of toxic brew. They are sometimes a hazard to livestock (actually almost all mammals) that might eat them because the Cantharidin is toxic. Horses, goats, cows, and sheep that eat alfalfa hay can get really sick with colic if there are even parts of dead beetles in the hay.

While we don’t really know exactly how Cantharidin is produced in the beetle, we do know these two things: 1) it’s produced in the male and transferred to the female during mating. 2) the female transfers Cantharidin as a protective coating for her eggs during oviposition. It’s believed that the first instar larvae (called triungulin) are equipped with a supply of Cantharidin as well.

After hatching, the triungulin crawl up onto flowers to hang out and wait to attach to the hairs of a visiting bee, riding back to its nesting site. The later developmental stages of larvae are protected underground or in holes in wood where native bees are developing. They consume the developing bee eggs, larvae and nest provisions (pollen and nectar).

Is there anything good about blister beetles? Well, strangely, the populations of some species of blister beetles are timed to coincide with grasshopper abundance. Adult blister beetles feed on grasshopper eggs. That’s good, right?

What else? Humans have used Cantharidin for years to remove warts and to remove tattoos as well. For ages, it has been used as a sexual stimulant. Even birds called Great Bustards have picked up on this! Read more here: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC6521026/

Blister beetles seem to be beneficial to some other species of beetles too. There is one beetle that actually has been found to chew on the blister beetle as a means of obtaining Cantharidin for its own protection. Other animals like toads, frogs, and armadillos are known to eat these beetles or use them in some way to confer protection. There is even a nuthatch that uses the beetle to “sweep” the wood where it wants to build a nest to protect it from parasites.

Back to my weekend sighting and collection of a few of these specimens. I had two that were intact enough to pin for my collection. I wore nitrile gloves to make sure I didn’t come into contact with any blistering agent. It’s a good thing I did. Some fluid made contact with one of the fingers of my gloved hand and actually started eating through it. That’s pretty caustic!

If you’re interested in more information about them, I’m happy to email some of my collected literature. There are also links you can check out in my previous post from April.

Thanks for reading!