Tiger Craneflies (Phoroctenia vittata angustipennis)

I finally got a few photos of these two after trying (and failing) in my attempts when I first spotted them on Sunday. Curiously, they were “bumping” onto tiny little cones on our fir tree, creating intermittent bursts of pollen with each “hit.” I wondered if they were perhaps eating pollen in advance of mating – with protein a necessary element in egg production.

These flies aren’t extraordinarily abundant. I checked my bug records, and the only other one I’ve seen in the yard was May 2, 2021. They are unique enough that I remembered looking them up and finding that the West Coast species is actually a subspecies, thus the 3rd name, angustipennis, tacked on to the binomial (Phoroctenia vittata).

Going back through my computer, I did find my previous source. Sometimes my computer filing system actually works and I remember to put labels and tags on my saved papers. It makes it so much easier to find them again! Re-reading the paper by Oosterbroek, Pjotr & Bygebjerg, Rune & Munk, Thorkild (2006), I was especially interested in their antennal illustrations, but found another part about the larvae interesting. They state, “the larvae of all these species develop in decaying wood of deciduous trees and might turn out to represent an especially significant conservation and monitoring element of the saproxylic fauna, as most of the species are rather scarce and some of them even very rare. Moreover, they are usually confined to old forests, orchards and similar habitats where there has been a long continuity of the presence of old, dying and fallen trees (Stubbs 2003).”

Our Landscape is Changing

The area near our home has remnants of older growth trees, though many are being cut and cleared for development, and the creation of homesteads. I worry that we will lose some of these species as the forests become more and more fragmented and the trees are more stressed with the advent of higher temperatures brought about by climate and landscape change. Yes, cutting trees = hotter spaces. We need trees! And bugs. Or will sorely regret our choices and actions when we are face to face with the reality of the great die-off of species.

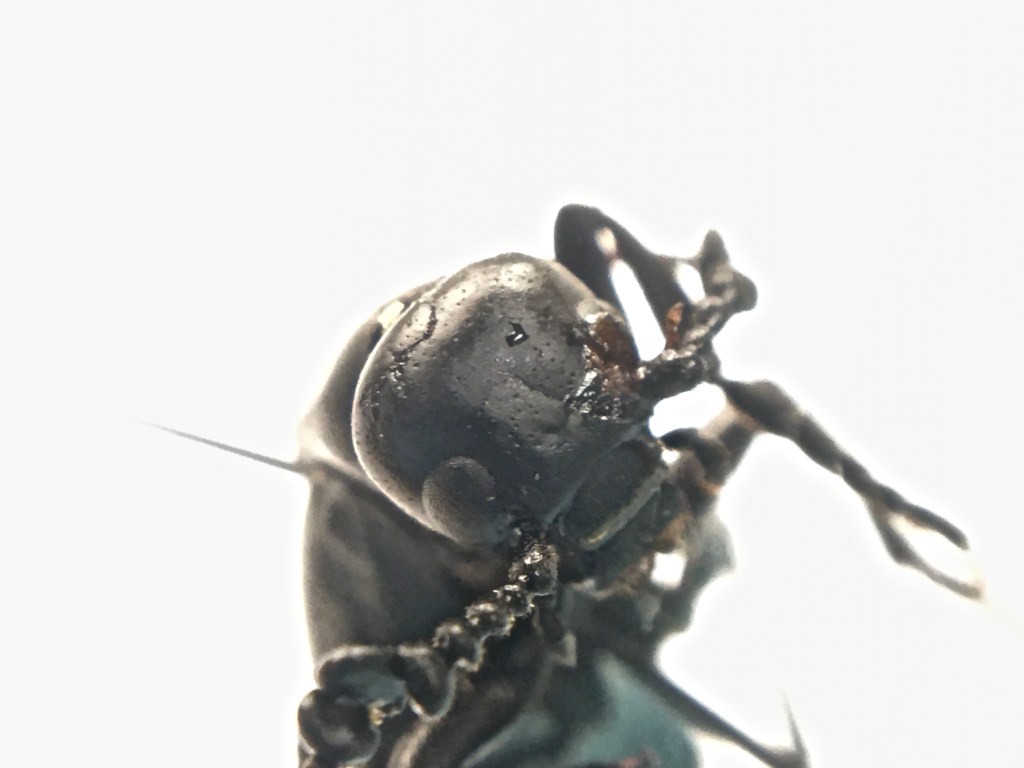

Back to the antennae for these Tiger Craneflies. Can you spot the male and the female in my photos? The male antennae are quite distinctive with their comb-like shape. Entomologists describe the comb-like antennae as Pectinate. If you haven’t figured it out yet, the male is the smaller of the pair. His antennae are wider, and he’s hanging on the bottom.

Why might craneflies be useful? Well, aside from population size being an indicator for forest ecological relationships, they make great food for wildlife, especially baby birds and their parents.

Isn’t nature amazing! Thanks for reading.

References and further reading

Saproxylic definition – https://www.amentsoc.org/insects/glossary/terms/saproxylic/#:~:text=Saproxylic%20invertebrates%20are%20those%20invertebrates,stage%20is%20dependent%20on%20wood.

Bugguide.net Subspecies Phoroctenia vittata angustipennis https://bugguide.net/node/view/109143

Oosterbroek, Pjotr & Bygebjerg, Rune & Munk, Thorkild. (2006). The West Palaearctic species of Ctenophorinae (Diptera: Tipulidae): key, distribution and references. IEEE Transactions on Information Theory – TIT. 138-149.

https://www.researchgate.net/publication/237714614_The_West_Palaearctic_species_of_Ctenophorinae_Diptera_Tipulidae_key_distribution_and_references