Fantastic Fly Friday, the Anastrepha Fruit Fly

Today I have a beautiful Fruit Fly (Genus Anastrepha) to show you. I found this specimen when visiting Tulum, Quintana Roo, MX in late January. The place we stay in Tulum has a swimming pool virtually no one ever uses. I love this place so much because I almost always have the pool entirely to myself. Everyone else is at the beach!

However, this particular pool is not maintained so well. More often than not, the filtration system isn’t turned on. I spend the first 15 minutes or so walking around in the pool to skim off all the bugs with a cup I bring from our room.

Unfortunately, my efforts to communicate, in broken Spanish, a request for a pool skimmer to the maintenance workers was a total failure. Probably they secretly referred to me as loco el bicho señora, or something like that. My Spanish is terrible. If you know me well though, finding bugs in the pool is literally one of the reasons I love staying at this place. I have my own vacay niche! Surveying for entomological diversity found in the pool.

There were more than a few bugs for me to “save,” that had landed on the water surface. Some, like this fly, had unfortunately already expired. I skimmed them all out, photographed them, then uploaded my observations onto iNaturalist. I even resuscitated a few that I thought were dead. Toilet paper or tissue paper “beds” work pretty well for drying them out in a pinch.

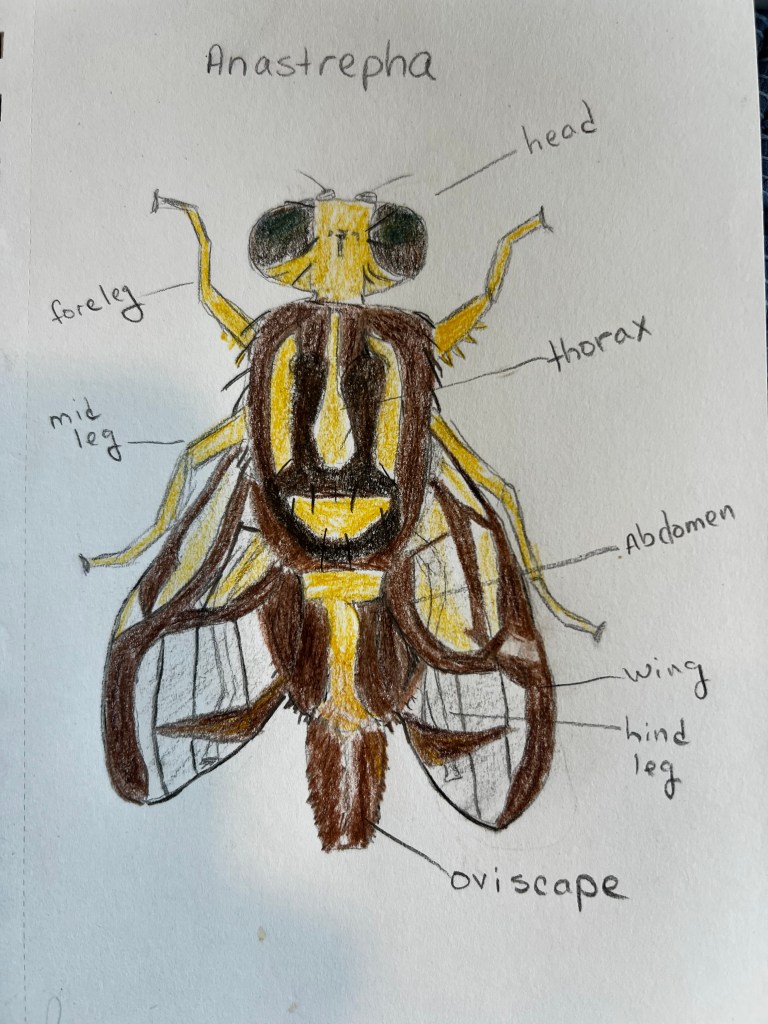

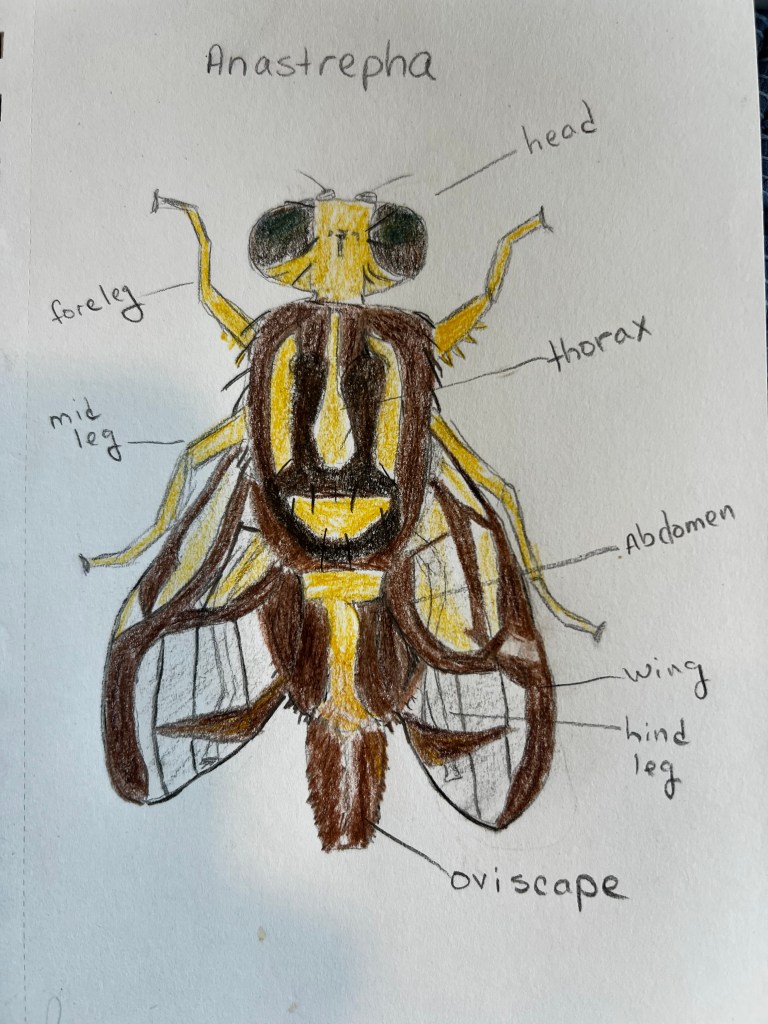

I collected these photographs because I really appreciated the cool picture window patterns on the wings. This is one characteristic of fruit flies. This is also a female specimen as you can see from the longish posterior appendage, her oviscape. Last week, I tried to create a space away from social media to decompress, so I sketched her (to the best of my ability) and used my colored pencils to bring her to life. Probably I did not get all her bristles in the right places. On flies, bristles are diagnostically quite important. I’m not quite there with my artistic rendering, but it was a relaxing activity.

In spite of their unique and beautiful wing patterns, fruit flies are often considered agricultural pests. Probably they wouldn’t be a pest except that we have these giant industrialized agricultural operations to feed more people than the planet should ever support, and probably, we artificially enable populations of various pests to explode because we are creating extra habitat for them. Fortunately, some targeted biocontrol and Sterile Insect Technique (SIT) has been effective enough to move producers away from utilizing harmful and unsustainable methods of chemical control, although I imagine some operations continue to apply pesticides.

This particular fruit fly is in the Genus Anastrepha. I haven’t really attempted going beyond genus level to identify this one to species. Anastrepha ludens, however, is a name that pops up often in literature from studies in Mexico and California. Anastrepha is a genus in the Family Tephritidae and I believe there are over 200 species of Anastrepha fruit flies in the Americas.

If you are interested in reading more about this genus, I would start off sending you to the 1963 study by Foote and Blanc, referenced below. I am currently waiting on a text I ordered from Abe Books on fruit flies, and will be doing additional reading once it arrives.

One interesting taxonomic tip I can leave you with: Tephritidae are true fruit flies. Those small flies that get into the bananas on your counter or into your rotting compost that many folks refer to as fruit flies aren’t fruit flies at all. They are vinegar or pomace flies, a completely different family called Drosophilidae.

Find out more when you follow me on Fantastic Fly Fridays!

References and Further Reading

Arias OR, Fariña NL, Lopes GN, Uramoto K, Zucchi RA. 2014. Fruit flies of the genus Anastrepha (Diptera: Tephritidae) from some localities of Paraguay: new records, checklist, and illustrated key. J Insect Sci. 1;14:224. doi: 10.1093/jisesa/ieu086. PMID: 25525098; PMCID: PMC5634125.

Baker, A. C. (Arthur Challen). 1944. A Review of studies on the Mexican fruitfly and related Mexican species. Washington, D.C.: U.S. Dept. of Agriculture. https://babel.hathitrust.org/cgi/pt?id=uva.x030450595&seq=3

Bugguide.net. 2026. Anastrepha ludens. Bugguide.net. https://www.bugguide.net/node/view/71452

Greene C. T. 1934. . A revision of the genus Anastrepha based on a study of the wing and on the length of the ovipositor sheath. (Diptera: Tephritidae) . Proc. Entomol. Soc. Wash . 36 : 127 – 179 .

Foote, R. H. and F. L. Blanc. 1963. The Fruit Flies or Tephritidae of California. Bulletin of the California Insect Survey 7: 1-117, 118 figs., 104 maps, colored frontis

Norrbom A. L. 2004. . Anastrepha Schiner (Diptera: Tephritidae) . http://www.sel.barc.usda.gov/Diptera/tephriti/Anastrep/Anastrep.htm .

Stone A. 1942. . The fruit flies of the genus Anastrepha , pp. 112. United States Department of Agriculture, Miscellaneous Publication 439 .