Bee Banter, part 1 – Honey Bees vs. Native Pollinators

The importance of Supporting Ecological Diversity

With spring around the corner, I thought it might be a good time to write up a post about bees. For those of you who don’t know me, I’ve been a San Juan Island resident now for over 17 years. When I was finishing my Masters Degree in Entomology and Nematology, I was required to take bee keeping as part of my advanced Apiculture coursework.

I won’t lie, I did enjoy the bees. I had one of the hives under a bedroom window, and it smelled so wonderful to open that window and smell the bees in the house. In my studies, I learned a lot about social insects. The other thing I learned was bee keeping sure is an expensive endeavor.

Why? Well mostly because the bees had to be replaced every year after they died over the winter from starvation. They didn’t always starve, but in the 6 years or so of keeping bees on the island, I think my longest surviving hive lasted about 4 seasons. That one, I can assure you, only lasted that long because I fed them sugar water. I was feeding the bees a quart of sugar water at least twice a day. They had all of that, and I never took any honey from my hives. All the costs added up. They also sting.

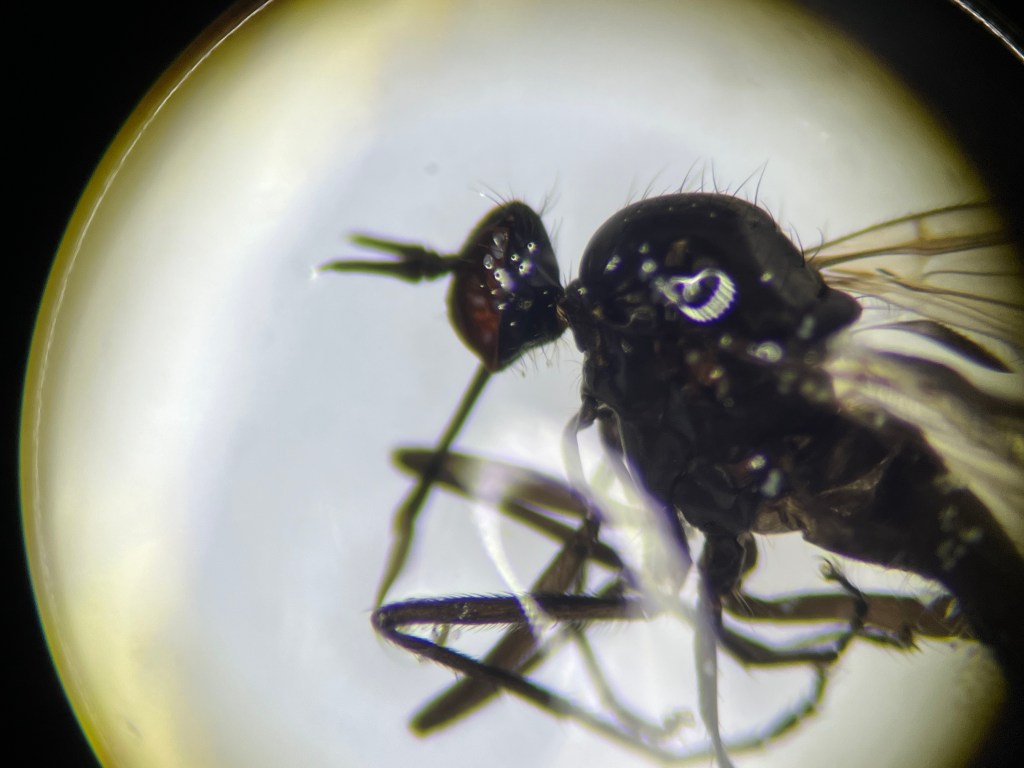

In my experience, I concluded honey bees weren’t exactly the best pollinators here either. As I spent more and more time in my study of insects and moved to a property with an old orchard (plums and apple trees), I saw the insects doing most of the pollination were flies. We have some incredibly cool species of flies too! At night, the insects pollinating these trees included many moths. Just an FYI, flies and moths are particularly attracted to the color white (same color as early flowering fruit trees).

Honestly, I am not much of a food gardener, but I do love watching for insects in our garden and observing the relationships that exist. Not just between the insects and the plants, but also the relationships between different species of insects (and I’ll lump spiders in here too).

Every year, I watch our resident chickadees and nuthatches glean insects off twigs and branches. Nature’s pest control. The little tree frogs gobble bugs off garden plants. Those same frogs are also food for a species of female mosquito. Yes, you might detest mosquitoes, but even mosquitoes are pollinators. Go out at night with a flashlight and look at those fruit tree flowers!

Even now, in February, I watch our year round, Anna’s hummingbirds zip along eaves of our home taking spider webbing to glue their nests together. They also eat many small bugs like fungus gnats and other small flies, even spiders!

If you just take a moment to look closely, there are many varied relationships between species at all trophic levels going on around us that have evolved to work in balance in our island ecosystem. Native species usually have multiple roles in the ecosystem. Some are pollinators, but also pest predators. Others we may consider pests, but they are also predators of pests. Most are food for some other organism in the food chain. Remember too, that just as we are healthier with a diverse diet, other organisms also stay healthy from sourcing nutrients from an assortment of food. When we lose diversity, we all suffer. We need a complex working ecosystem, and that comes from nature!

Some of our island native bee pollinators include bumble bees, sweat bees, alkali bees, blood bees, orchard bees, leaf cutter bees, nomad bees, digger bees, fairy bees, and others. These bees may not produce honey, but they are pollinators of immensely great value.

In fact, research over the past decade is illuminating just how critical these native bees and other native pollinators are for biodiversity. Biodiversity that is disappearing from our world due to habitat loss, land use changes, agricultural practices, and competition over resources with non-native species (like honey bees). You don’t have to take my word for it though. The Washington Native Bee Society and the Xerces Society will give you similar information.

Try Googling a bit on your own and you might find some pretty cool statistics about how native bees are actually better pollinators than honey bees, AND that their pollination services can yield larger, healthier fruits (like blueberries and strawberries for example). Competition over resources and displacement of native bees due to honey bee keeping isn’t limited to our island or our state. It’s been something happening world wide where honey bees are used for agricultural practices, whether for pollination or honey production. The encouraging news is that supporting native pollinators is gaining momentum. I’ve compiled a resource list for you to look at, read, and share if you are inclined.

If you are still dead set on setting up a honey bee hive, I’m happy to walk you through it. I can give you a list of everything you’ll need, provide the cost of all those supplies, and advise you on how not to get stung, why you should never eat a banana near your bee hive, what problems you can anticipate with pests and pathogens, and how to avoid losing your bees due to swarming. I will also tell you that if you set up a honey bee hive, you must file and register your colony with WSDA per state law. Hopefully, you will make your way to the same conclusion as I have. It’s cheaper and also ethically responsible to support native pollinators and conserve habitat in your own yard for pollinator diversity. It’s also quite fun and rewarding to watch and learn about native bees and the bugs you probably never even knew existed.

References and Further Reading

Anderson, H. L. D. (2024). Nocturnal moth communities and potential pollinators of berry agroecosystems in British Columbia (T). University of British Columbia. Retrieved from https://open.library.ubc.ca/collections/ubctheses/24/items/1.0447737

Brast, C. 2024. Where are all the Bees? Bugging You From San Juan Island. https://buggingyoufromsanjuanisland.com/category/bees/

Brast, C. 2022. Musings on the complicated topic of native pollinators, food production, and climate change. https://buggingyoufromsanjuanisland.com/2022/08/17/musings-on-the-complicated-topic-of-native-pollinators-food-production-and-climate-change/

Brast, C. 2025. Fantastic Fly Friday. https://buggingyoufromsanjuanisland.com/2025/04/11/fantastic-fly-friday/

Dlugo, J. 2022. Seven Native Bees to Know in Washington State. Washington Native Bee Society. https://www.wanativebeesociety.org/post/seven-native-bees-to-know-in-washington-state

Hatfield, R. And M. Shepherd. 2025. Want to save the bees? Focus on habitat, not honey bees. Xerces Society. https://www.xerces.org/blog/want-to-save-bees-focus-on-habitat-not-honey-bees

Hatfield, R., S. Jepsen, M. Vaughan, S. Black, and E. Lee-Mäder. 2018. An Overview of the Potential Impacts of Honey Bees to Native Bees, Plant Communities , and Ecosystems in Wild Landscapes: Recommendations for Land Managers. 12pp. Portland, OR: The Xerces Society for Invertebrate Conservation. https://www.xerces.org/publications/guidelines/overview-of-potential-impacts-of-honey-bees-to-native-bees-plant

KEARNS, C. A. 2001. North American dipteran pollinators: assessing their value and conservation status. Conservation Ecology 5(1): 5. [online] URL: http://www.consecol.org/vol5/iss1/art5/

MacInnis, G, Forrest, JRK. 2019. Pollination by wild bees yields larger strawberries than pollination by honey bees. J Appl Ecol. 56: 824– 832. https://doi.org/10.1111/1365-2664.13344

Mallinger, R.E. and Gratton, C., 2015. Species richness of wild bees, but not the use of managed honeybees, increases fruit set of a pollinator-dependent crop. J Appl Ecol. 52: 323-330. https://doi.org/10.1111/1365-2664.12377

Angelella GM, McCullough CT, O’Rourke ME. 2021. Honey bee hives decrease wild bee abundance, species richness, and fruit count on farms regardless of wildflower strips. Sci Rep. Feb 5;11(1):3202. doi: 10.1038/s41598-021-81967-1. Erratum in: Sci Rep. 2021 Aug 17;11(1):17043. doi: 10.1038/s41598-021-95368-x. PMID: 33547371; PMCID: PMC7865060. https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC7865060/

Page, Maureen L., and Neal M. Williams. 2023. “ Honey Bee Introductions Displace Native Bees and Decrease Pollination of a Native Wildflower.” Ecology 104(2): e3939. https://doi.org/10.1002/ecy.3939

Lorenzo Pasquali, Claudia Bruschini, Fulvia Benetello, Marco Bonifacino, Francesca Giannini, Elisa Monterastelli, Marco Penco, Sabrina Pesarini, Vania Salvati, Giulia Simbula, Marta Skowron Volponi, Stefania Smargiassi, Elia van Tongeren, Giorgio Vicari, Alessandro Cini, Leonardo Dapporto. 2025. Island-wide removal of honeybees reveals exploitative trophic competition with strongly declining wild bee populations. Current Biology. 35(7) : 1576-1590.e12,

ISSN 0960-9822, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cub.2025.02.048 https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S0960982225002623

Thomson, D. (2004), COMPETITIVE INTERACTIONS BETWEEN THE INVASIVE EUROPEAN HONEY BEE AND NATIVE BUMBLE BEES. Ecology, 85: 458-470. https://doi.org/10.1890/02-0626